It must have been sometime in 1953 that I recall my parents discussing the prospect of leaving Majorca.

My mother, Cynthia, had recently suffered a miscarriage that nearly took her life. It appeared that the initial procedure had been flawed and the packing material used to staunch the bleeding had not been removed. This material had begun to turn septic seriously endangering her life. Efforts to save my mothers life necessitated the removal of her reproductive organs. Cynthia’s death was narrowly averted, but my parent’s hopes of conceiving another child were dashed.

I can only imagine the bleak discussions between my parents, as they considered their situation. It had become abundantly obvious that medical services in Majorca were inadequate. In addition, it was clear that my sister, Diana, had outgrown her home schooling with her German tutor, Maria Frank.

On a more positive note, news came from America that Senator McCarthy had been exposed as an alcoholic. His claims to have evidence of a communist cabal evaporated. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings turned into a witch hunt fueled by innuendo and unsubstantiated character assassination.

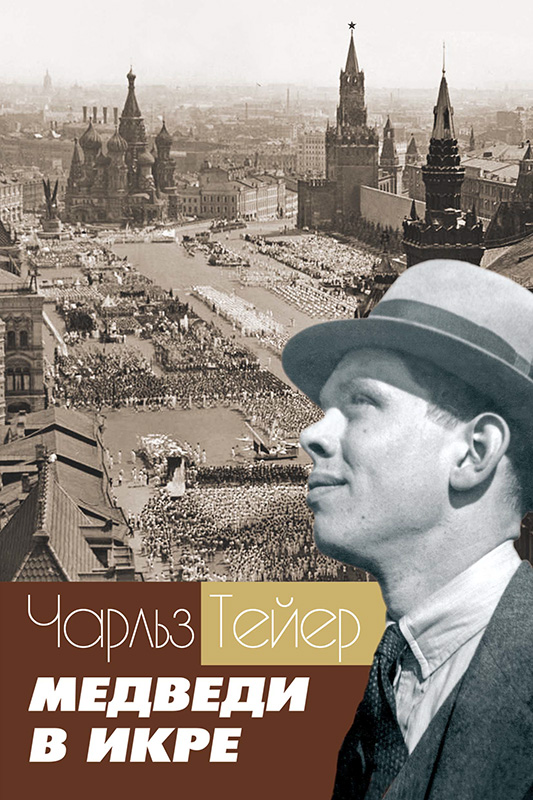

Having refused to defend Charlie’s reputation prior to the HUAC hearings, the Foreign Service now invited him to return to the diplomatic corps. Hung out to dry in the run up to the HUAC hearings, Charlie was in no mood to accept this craven sop. Besides, his recently published book about life in the foreign service was turning out to be quite a commercial success – much to the chagrin of his erstwhile detractors.

With the cold wet winds sweeping across the Mediterranean Sea and whistling through the drafty house, my parents began to make plans to return to Munich, which had been their home prior to their Majorcan retreat.

Our sojourn in Majorca had begun two years earlier. In 1952, my father had flown back to Washington DC to defend himself against accusations that as one of our top diplomats, he had become a “communist sympathizer” – a charge that stood in stark contrast to his record as a graduate of West Point, and the first US diplomat to open an embassy in Moscow. Charlie was always ready to investigate conditions where ever he was posted, whether it was rumors of famine in the Ukraine, locating caches of counterfeit money or coordinating battlefield progress with Yugoslav partisans.

But overseas experience had come at a cost, since he had little experience dealing with either the postwar administration of our foreign policy, or the build-up of the Cold War.

At that time, Charlie was serving as the top civilian administrator for the American occupation zone (effectively the “Governor” of Bavaria and Austria), when he was accosted by Roy Cohen (one of Senator Joe McCarthy’s chief investigators) and interrogated about an affair Charlie had had several years earlier. Incensed by the intrusion into what he perceived as his private affairs, he had Cohen ejected from his office, and called Senator Joe McCarthy a “son of a bitch” for good measure. This insult was to blossom into a bitter feud that redounded to Charlie’s disadvantage as the Senator prepared to question him in the nationally broadcast House Un-American Committee (HUAC) hearings.

But Washington DC was in a frenzy over Senator Joe McCarthy’s claims that our Foreign Service had been infiltrated by hundreds of Soviet agents. As one of our nation’s top Soviet experts, my father was at risk of being dragged before this witch hunt. Faced with the public humiliation of having his name dragged through the mud, my father submitted his resignation and left the country.

The FBI immediately “black balled” him making it impossible to earn a living in the United States. Faced with a subpoena that would restrict his ability to return to Munich he flew back to Munich to consider his family’s options. Faced with penury, my parents decamped for Majorca – the cheapest place they could find in Europe.