In 1952 amidst a paroxysm of anti-communist witch hunts my father leased an isolated house tucked into a craggy cove called Cala San Vincente on the remote Mediterranean island of Majorca. The traditional Majorcan house was notable for its white brick walls, and its red tiled terraces. The house was accessible by means of a narrow goat track that twisted along for five km to Porto Pollensa. Built into the rocky hillside it was surrounded by almond groves and citrus orchards. The house was swathed in colorful bougainvillea.

The Balaeric Islands first came to the attention of the British during the Napoleonic wars when they were occupied by the British Navy. It is to these nautical imperialists that we owe the invention of Mayonnaise which was quite literally whipped up in Mahon to honor a visiting Admiral. In the early twentieth century these idyllic fishing communities attracted poets, painters and writers like Robert Graves, Gertrude Stein, Anaïs Nin, and Ernest Hemingway among others. Now they sheltered a new generation of exiles.

Black balled

Despite the warm tropical setting, this sojourn in the Spanish sunshine was no idyll for my parents. This was a hideous time when US diplomats assigned to manage our far flung alliances were attacked by US politicians to advance their domestic political agendas. This was the era of anti-communist witch hunts in which diplomats were expelled from public service solely because diplomatic exigensy demanded it.

Responsible for managing our countries’ relations with friends and foes alike, diplomats often found themselves shunned when alliances shifted. Since time immemorial, diplomats have been sensitive to the risk of backing the wrong horse, or becoming too closely associated with the policies of either party. Those that risked these political shoals could find themselves unwelcome at home, professionally unemployable or “black-balled” by the FBI. Some Foreign Service Officers left government service and embarked on commercial endeavors. Others chose inexpensive locations where they might sit out the ebbs and flows of political change as cheaply as possible. Such was our situation in early 1952.

Fearing further retribution from Senator McCarthy my parents wound up their affairs and purchased a Jeep and trailer. With the Jeep and an old Buick they assembled a modest convoy and hurried south from Munich to Barcelona. After an eight hour ferry ride they arrived safely in Palma in the Balaeric Islands. The next day they finally reached their destination in Cala San Vicente, about 5 kilometers northeast of Polenća. For the next two years this was to be home.

A Welter of Languages

With the Cold War encroaching, opinions were hardening and diversity was withering on the vine. Many of our most experienced diplomats in China, Russia and Eastern Europe were getting the cold shoulder in Washington, pressured to resign or forced into exile. But pulling up stakes was no simple matter.

Over time, many of our veteran diplomats had acquired experienced domestics, whose familiarity with diplomatic protocol, as well as their knowledge of local customs and language made them essential to managing a diplomatic post. In our case, we were assisted by Maria and Pepe Polar, a Majorquin couple that worked for us for more than ten years. In addition Diana’s tutor, Maria Frank, came to educate both Diana and myself in German. In this era before the widespread adoption of English as the de facto international language, we relied heavily on local domestics to manage our daily needs.

Learning to converse was no simple matter in our household. Inasmuch as each part of the house served a distinct purpose, it reflected the linguistic preferences of its inhabitants. The upstairs bedrooms, the living room and the study were reserved for our English speaking parents. My sister, Maria Frank and I conducted our noisy activities to the clipped precision of German. In the kitchen the household staff spoke Spanish with us and Majorquin, the local patois, when conversing amongst themselves. As a result of this polyglot mixing of words and languages, I became convinced that words could be further differentiated according to general usage. Thus objects found in the kitchen tended to be expressed in Spanish, while familial subjects were best shared in English. German was reserved for serious discussions. As a consequence, my conception of “language” was a bit fluid and it tended to confuse anyone not accustomed to speaking multiple languages at once.

Cherries

Not only were we isolated from family and friends, but it soon became clear we were beyond the reach of modern medicine. Sometime during the spring of 1953 I developed intense stomach pains and the local doctor was consulted. After examining me the doctor declared that I had contracted polio. Happily he reported that he had procured some of the recently available antibiotic: penicillin. He promptly injected a dose into my right leg. No sooner had the penicillin begun to spread down my right leg than I went lame. This convinced him that the penicillin was working. He urged my mother to inject another dose in my left leg, but my mother was having none of it. With no other options available, she appealed to the American Embassy in Madrid and they sent a military plane to fly me to the US army hospital in Madrid. There the doctors examined me and to their horror discovered that I had been given six times the adult dose. Had they given me that second dose, I would have gone permanently lame in both legs. As it was, I was unable to walk on my right leg for several weeks. In the end the American doctors determined that the cause of my stomach ache was that I had consumed a plate of cherries including all the pits and stems. To this day, I still avoid eating cherries.

The Susurration of late night conversations.

The incidents chronicled in this early period of my life are mostly recollections of stories recycled amongst friends and family. A few actual memories are derived from direct recollections indelibly etched into my memory. I can still recall the “grown-ups” gathering around the kitchen table as my father recalled one improbable adventure after another. My eye lids would grow heavy, as the wood crackled fitfully in the hearth and the familiar aroma of cigarettes would lull me to sleep. Around the wooden table a cluster of shot glasses surrounded a wounded bottle of Johnnie Walker. Drawing out another cigarette, my father would straighten up in preparation for yet another hilarious anecdote. But this time my mother’s cough would signal an abrupt change of direction. Casting significant glances around the table she would announce that “little pictures have big ears.” That was the signal for my departure despite my entreaties to remain “just a little bit”. Thereafter the recollections faded quickly as I was deftly bundled off to bed. Try as I might, my memories faded into black as I sank into the pillow and the distant conversation slipped into dreams.

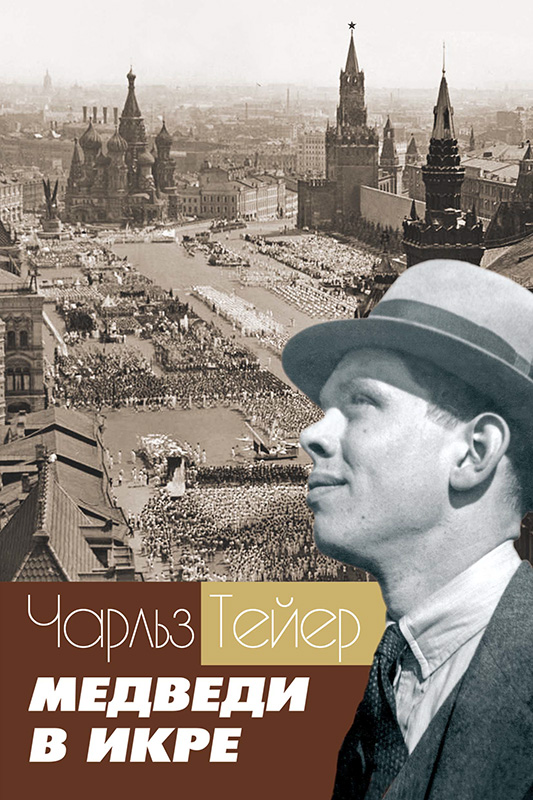

In these early chapters I have alluded to prior events that laid the basis for our unusual isolation. For those interested in the vicissitudes of my father’s adventures I recommend “Bears in the Caviar”, and “Hands across the Caviar”. They provide ample details of my father’s extensive travels through Russia, Easter Europe and Central Asia. I highly recommend these books to fill in the foundation of our exile in Majorca and subsequent adventures far beyond my childhood dreams.

A Career Derailed

In 1952 my father was a highly regarded US Foreign Service Officer looking forward to his appointment as the first US Ambassador to Yugoslavia. Just two years earlier he had married Cynthia Dunn, the daughter of the American Ambassador in Rome. Cynthia had a daughter, Diana, from a prior marriage who was 7 years older and shared many of my childhood adventures. In 1951, Cynthia gave birth to me and named me after my grandfather, Ambassador Jimmy Dunn.

Charlie’s career was proceeding smoothly until word of his unusual contributions filtered back to Senator Joe McCarthy. At first Charlie ignored the queries coming from the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). But having spent most of his career overseas he badly underestimated the danger that Senator McCarthy’s power of the Senator and HUAC. He further aggravated the situation by publicly calling McCarthy “a son of a bitch”.

Matters were not improved by allegations that Charlie had fathered a child under hurried circumstances. Homosexual liaisons were also rumored. Charlie returned to Washington DC to defend himself just as Senator McCarthy announced plans to hold nationally broadcast hearings. A subpoena to force his testimony appeared imminent. Fearing that such a hearing might turn into a nationally broadcast spectacle, Charlie hurriedly flew back to Munich.

Within a year, Charlie and his young family were forced out of the Foreign Service and “black-balled”. Unable to secure employment in the United States my parents reviewed their paltry finances and realized that they needed to relocate to where they could subsist on a meager income. Along with their children, they were being forced into exile. After much deliberation, Cynthia and Charlie decided to decamp for the Balaeric Islands of Majorca.

Majorca was a long way from Washington, where the the State Department machinations were determining my father’s future. His strenuous efforts to reverse his misfortunes seemed to melt in the torpor of the Mediterranean sun. Often it took weeks to get responses to their letters. Visitors were rare and uncertainty filled the sun bleached void.

In those days Foreign Service families often included an extended staff. Our entourage included my sister’s governess, a Majorcan couple (that served as our maid and butler). And of course, a menagerie of dogs, birds and even a donkey. Pulling up stakes was becoming more complicated.

Maria Tina

Our donkey was endlessly useful, be it hauling groceries from the village to clearing the detritus collecting under the olive groves. Maria Tina was a patient beast, but on occasion was known to kick. I do recall one instance, when she knocked me down on our dusty court yard. I was so incensed that I picked myself up, marched over to her and tried to kick her back. I soon learned to respect her space; especially her back side. Our servants, Maria and Pepe Polar would sit on the steps laughing as they watched this collision of my unstoppable energy and Maria Tina’s stubborn immovability. Eventually the donkey got used to my noisy antics and simply ignored me. I too, modified my furious assaults in the face of the unwavering resistance. Yankee determination, it seems, had no chance in the Mediterranean climate.

Saharan Dust.

By 1953 Senator Joe McCarthy’s allegations had been debunked and his investigations discredited. But for many of his victims it would take years to re-establish their careers.

In Cala San Vicente, our family had just begun to carve out a new life. The winter brought chilly nights and rough seas that ravaged the colorful fishing fleets. By day the gritty sirocco winds would blanket the arid islands with a fine red coat of Saharan dust.

Mastica, mastica!

When I was old enough to eat at the table, I was included in our familial gathering. However, there were hitches on this road to acquiring the “manners” necessary to eat alongside the adults. Being a “picky” eater I soon developed a strategy to avoid eating my “greens”. This entailed stuffing my mouth with as many of the loathsome vegetables my mouth could accommodate and then slowing my eating to a near stand still. Eventually, this strategy resulted in my banishment from the dinning room, and I was relegated to the kitchen steps to finish my meal.

“Mastica, mastica” Maria urged to no avail. Chew, chew, she kept insisting. On and on we struggled, until I had reduced the offensive greenery into a solid ball. By then the “veggie delight” had been thoroughly disintegrated and Maria relented. I can still remember these gruesome contests like they were yesterday.

La Casita

One day late in 1953, my sister Diana took me up into the garden where she had furnished her “Casita” (little house) to resemble a pharmacy. My mother had been given her an extensive assortment of pills designed to diagnose the presence of various illnesses common to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

Not having any immediate use for this trove of bottles, she gave Diana permission to use them in her “pharmacy” – under the strict admonition that she was NEVER to eat any of them. Diana was about 10 years old at the time, and dutifully agreed to the conditions. But I was only two and had never agreed to any such conditions. To safeguard her “Casita”, Diana had forbidden me to enter her little bodega thus, making the prospect of looting it irresistible.

In those days the danger posed by pills were not clearly understood, especially since medicinal cures traditionally came in the form of injections, ointments and herbal cures. Pills, as we know them today were unknown to the inhabitants of Majorca in the mid-fifties.

Diana’s colorful stash of brightly colored pills was probably the remains of a WW2 diagnostic field kit used to determine what illness the soldier had contracted. The wide assortment of colored pills corresponded to the rich array of illnesses that the patient might have contracted. After ingesting one of these pills the patient’s urine would turn the same color as the pill, signalling that the suspected malady was NOT present. After a few days the urine would return to its original color, with no ill aftereffects. But without any prior explanation the immediate effects were dramatic, especially when administered simultaneously to a sizable group of people.

Thus, the blue pill I munched down to convince the servants of their beneficial effects turned my diaper blue. Since I was tightly swaddled in a leak proof diaper, the alarming consequences went unnoticed – at first.

No doubt my elder sister had been warned that she was never to ingest any of these pills, and she has faithfully kept her promise. But that admonition had failed to impress me. Besides raiding my sister’s illicit medicinal stash sounded like a fine adventure. So it was, that I arrived in the kitchen with pockets full of multicolored pills. What better way to show off my booty than to share it? Not being one to hoard my treasures, I plundered all the colorful pills I could find and promptly shared these “candies” with the household staff. The afternoon progressed uneventfully until the staff became increasingly uneasy. Eventually they began to share their concerns with each other.

“Really, your’s is blue? Mine is orange!” It didn’t take long for them to connect this disturbing symptom witth my “candies”. Word spread throughout the kitchen and eventually Pepe appeared sheepishly at my father’s study. Quite embarrassed, he recounted the afternoon’s events and that he had been delegated to raise the matter with “El Senor” to see if he could help shed some light on this spontaneous outbreak of urinary discoloration.

My father immediately recognized the tell-tale signs of Jimmy’s handiwork. Indeed, when he was summoned, Jimmy cheerily recounted how happy the staff were to get these “candies”. Asked whether he had experienced any unusual after effects, Jimmy was a bit puzzled, but upon closer inspection it was found that his diapers had also turned bright blue. Happily, no one was suffering anything more serious than embarrassment. Unfortunately, I had my amateur pharmacist’s license revoked and Diana had to restock her “Casita” with less attractive wares.

All this seclusion on a desert island may sound romantic and reminiscent of Gerald Durrell’s stories of his childhood on the island of Corfu during WW2, but the reality was pretty grim for my parents. One constant danger was the abysmal level of medical knowledge and practice. In fact, my mother nearly died due to the primitive post natal care available in the island’s only hospital in Palma.

Smugglers

One memory in particular stands out. It must’ve been after my normal bedtime, because it was growing dark when Pepe took me by the hand and we ascended to a high balcony that faced out to the sea. Below us our red tiled roof spread out under the olive trees that clung to the steep slope. Pepe and my father were discussing some sort of purchase as we sat in the waning light. Time seemed to crawl as the water in the cove turned from its day time azure to a steadily darkening blue and then it dissolved into a stygian blackness. I may have fallen asleep because I remember being awoken at some point.

Pepe was busily fiddling around with one of the storm lanterns we used when the winter storms cut our electricity. A tiny butterfly of flame fluttered weakly as Pepe replaced the glass mantle. A few moments later he had the lantern burning brightly. Carrying the lantern to the seaward side of the balcony, Pepe began to swing the lantern back and forth. Every so often he would pause to peer out towards the entrance of the cove. Finally, after what seemed an age Pepe whispered something to my father, and he, too, began to scan the dark horizon. Pepe reached down and held me up so I could see over the parapet. There, near the entrance to the cove I glimpsed a tiny light bobbing frantically on the dark waves. Pepe resumed waving the lantern back and forth until it was clear that the boat had spotted our signal. Taking me by the hand we descended to the ground floor and continued down a path to the shore.

We stood there in the dark with the waves lapping at our feet for what felt like an eternity. Eventually, I began to hear the noise of oar locks creaking rhythmically as a rowboat approached the beach. Someone jumped out into the waist-deep water and came up the beach. Pepe went to meet him exchanging greetings in the ubiquitous Majorquin dialect. A list of items was discussed and substitutions relayed back to my father who stood just above the surf line holding me. Money exchanged hands and assurances conveyed regarding their return a week later, whereupon the sailor turned and pushed the prow of the boat back out through the combers that were surging up the beach. In the gloom of darkness the figure jumped back aboard the craft and it soon soon disappeared into the surging water. In a few minutes even the squeaking of the oarlocks was swallowed up by the hiss of sand sizzling across the windswept beach.

The following week Pepe leaned over to whisper in my father’s ear as he served dinner. Papa asked if I wanted to see what the smugglers had brought. Of course, I was not going to miss another night time adventure. This time we walked down to the beach and waited until darkness had fully engulfed us before lighting our lantern.

Adios

Knowing what to listen for, I now concentrated to discern the approaching craft amidst all the other night time sounds. And there it was: the faint rhythmic creaking of leather oarlocks and the subtle slicing of a keel over the gently lapping waves.

Once pulled up on the beach Pepe examined the goods and paid the swarthy seamen. Speaking majorquin in low voices Pepe negotiated future assignations and details of what we were anxious to procure at their next meeting. The conversation was brief as the seamen were anxious to avoid the Guarda Civil that regularly patrolled the myriad inlets and small coves. The transaction was quickly completed. One of the boatmen grasped the bow and pushed the dingy into the oncoming serf. In less than a minute the boat was swallowed by the darkness.

“What did you get Papa?”, I inquired.

“The necessities”, he replied tersely.

“What are the necessities?”

“Cigarettes, whiskey and soft toilet paper”.

*******************************************************************************************

Much of the source material and Charles Thayer’s private papers reside in the Truman Library. These include many photographs and private letters that helped me bring the later period of his life into focus. In addition, Charles Thayer was a prolific writer who published the following books and articles based on his extensive experience in Europe and Russia:

Bears in the Caviar (1951)

Hands Across the Caviar (1953)

Unquiet Germans (1957)

Diplomat (1959)

Moscow Interlude (1962)

Guerilla (1963)

Checkpoint (1964)

He also wrote a book about his mother, Muzzy (1966).